Chancellorship Dates

July 1, 1954 - June 30, 1968

BORN

October 9, 1915 - Knightstown, Indiana

DIED

April 4, 2010 - Lincoln, Nebraska

ARTIFACTS

- Clifford Hardin Nebraska Center for Continuing Education

SOURCES

- "Prairie University," Robert E. Knoll

- Clifford Hardin, 94, dies; agriculture chief under Nixon

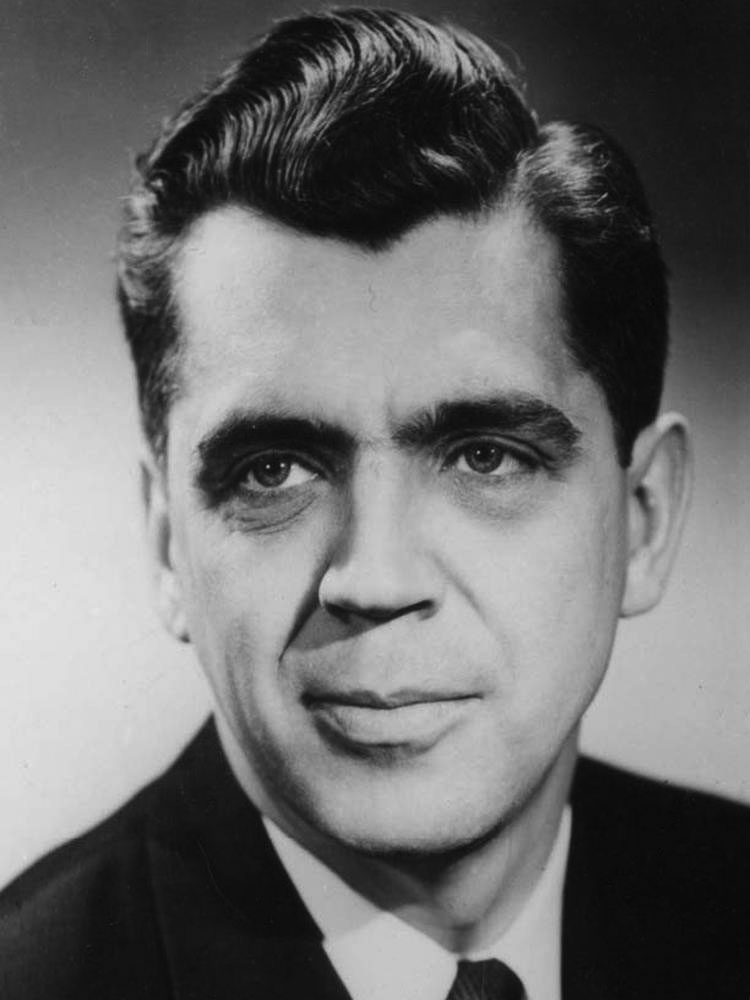

Clifford Morris Hardin, then Dean of Agriculture at Michigan State University, was named chancellor of the University of Nebraska in 1954, at the age of 38. At the time of his appointment, he was the youngest university president in the country. He joined a university that was poised for greater things, but his ambitions, at first, seemed modest. For his opening address to the faculty, Hardin spoke of making the University of Nebraska the friendliest university in the country.

From that perhaps-inauspicious start, Hardin began to remake the university. Within his first month as chancellor, he had begun the process of applying to the Michigan-based Kellogg Foundation for a national extension center. Despite considerable local inertia, if not direct opposition, Hardin secured the Kellogg funds and led the effort to raise local matching resources. The Nebraska Center for Continuing Education was dedicated in 1961 and the building at 33rd and Holdrege Streets is named for Hardin today.

Nebraska, a national power in the early days of college football, had fallen off the map in the sport. Hardin entered an institution on an upward academic trajectory that was saddled with a marquee athletic program that was only muddling through.

During his time at Michigan State, Hardin had become acquainted with Duffy Daugherty, the Spartans' coach. Looking for a new coach at Nebraska, Hardin's first instinct was to see if Daugherty was interested in the job. An institution already in East Lansing, Daugherty declined, but he pointed west to Wyoming, where a former Spartan assistant was leading the Cowboys' team – Bob Devaney. Hardin pursued him, and won him over. Over the next 35 years, Devaney and his protégé Tom Osborne built a program seldom equaled in athletics. For Hardin, it wasn't really about football. When interviewed in the New York Times in 1983, Hardin said, "I felt the state needed something to rally around. If we could pull this off, it could be the difference. I think, in retrospect, it probably helped us get more money to build the university."

The final phase of Hardin's tenure was marked by the complex set of negotiations that would attend the birth of the University of Nebraska system. By 1966, the Municipal University of Omaha was was facing serious financial distress. It had been a city-supported public institution since 1937, but taxpayers refused to adequately fund it; in desperation its president appealed to the Legislature for support. Legislators representing the city of Omaha wielded considerable power in the Legislature, but they were not a majority. Nevertheless, ideas were floated, including one to create a separate state-funded university complete with its own regents. Hardin, seeing no positive aspects to the prospect of two completely-separate institutions competing against each other for scarce state resources, began talks with members of the Board of Regents, with the Municipal University's governing board, and other state leaders; the complex set of negotiations would end with three institutions (University of Nebraska–Lincoln, University of Nebraska Omaha, and University of Nebraska Medical Center, each with a president, under one Chancellor. On July 1, 1968, Hardin's chancellorship of the University of Nebraska, before then the name given to the flagship institution in Lincoln, transitioned to encompass leadership of the University of Nebraska system; Joseph Soshnik was appointed to head the flagship institution in Lincoln as its president. (These titles were reversed in August 1971.)

Hardin’s tenure as Nebraska chancellor would end rather abruptly, as in January, 1969 he was tapped as Secretary of Agriculture in the incoming Nixon Administration; he thought the post temporary, and initially took a leave of absence to serve in Washington, but would resign the Nebraska position that summer.

Hardin's legacies at Nebraska are far-reaching and started with a sizable increase in the size of the university and in its stature, tripling in attendance over his tenure, and reasserting itself as one of the nation's leading institutions in research and graduate education. The institution's fame would be immeasurably increased by the seed he had planted in his hire of Bob Devaney, who would lead the Cornhuskers to two national championships (1970 and 1971), and set the stage for the most dominant five years (1993-1997) in the modern history of the sport, a 60-3 run under Devaney's assistant Tom Osborne, during which three national championships were won. Hardin molded great leaders wherever he went. According to an obituary in the Washington Post, 13 administrators who worked under him at Nebraska went on to lead universities themselves. And two who assisted him while he was Secretary of Agriculture went on to themselves serve in the post.

Hardin would return to Lincoln in his retirement, where he died on April 4, 2010, at the age of 94.